Overview

Celebrating Michael Kidner's (1917-2009) diverse and distinctive relationship with colour, works from the early career of the renowned British artist are installed in our Kingsland Road windows, complementing a display of later pieces at the recently-opened Maggie's Centre in north London, designed by Daniel Libeskind.

Exploring a significant development of painting in the 1960s which relied upon geometric forms to provide optical effects, through mixed media Kidner's extensive oeuvre bridges the constructs of art, science, mathematics, and theories of chaos. Optics presented Kidner with a challenge in his pursuit of a pure form of imagery, seeking a phenomenological approach to the fluctuating effects of light and colour within the space set by the canvas, with the artist reflecting “unless you read a painting as a feeling then you don’t get anything at all.”

Exhibited at Kidner’s first solo exhibition at St Hilda’s College, Oxford in 1959, the After Images series was influenced by Mark Rothko’s colour field paintings, exploring colour as a pure subject, interest and spectacle.

In Grey rectangle on yellow - After Image (c.1959), Kidner contrasts the centre of the work against a predominantly yellow background, creating the sense that the grey is drifting in an ambience of colour in front of the canvas. Marking the artist's move from figuration and landscape, the painting influences the eye's retina to make the central shade appear brighter than any surrounding background. Kidner describes colour in the series as ‘sensations proceeding from its nature, from its inner mysterious force.’

Two halves of a circle are divided in Split Circle, Red, Green Two (1960), with a thin gap preventing them from becoming whole. The red half floats upon a deep pink background, while the grey is barely discernible against the solid black. The composition compels the viewer to connect the two arcs, however the structure of the work implies there is an energetic repulsion between the two, forcing the sides apart.

Red China (1966) is an example of Kidner’s exploration of continuous waves, supported by his striped paintings constructed from two alternating colours. This period was significant as it symbolised Kidner's turn towards creating rational art while the physicality of a wave interested Kidner as a pattern, generating more visual prospects than a straight line. With the wave's potential to be woven within and out of phrases, resulting in optical effects separating colour and form, there is an allusion to both the conception and culmination of a sequence, with the work implying the wave's rhythm is at once limited and infinite.

The title and the date reference the political state of China, as 1966 marked the inception of the Cultural Revolution by the founder of the People’s Republic of China, Mao Zedong, resulting in a decade-long period of social and political unrest. Kidner’s use of red both in the title and the painting signifies the domination felt throughout China and the violence caused by the political purification.

Although Kidner’s work is not inherently political, throughout his career he confronted the irrationality of humanity playing out in the disasters of the 20th century. Constructing rational methodologies that unearth the fundamental sequences of the world, Kidner was interested in science and reason for its value as a moral and ethical consideration. Believing in the importance of logic and reason to improve social issues, Kidner's conversion of waves into form reflected a poignant human need for harmony.

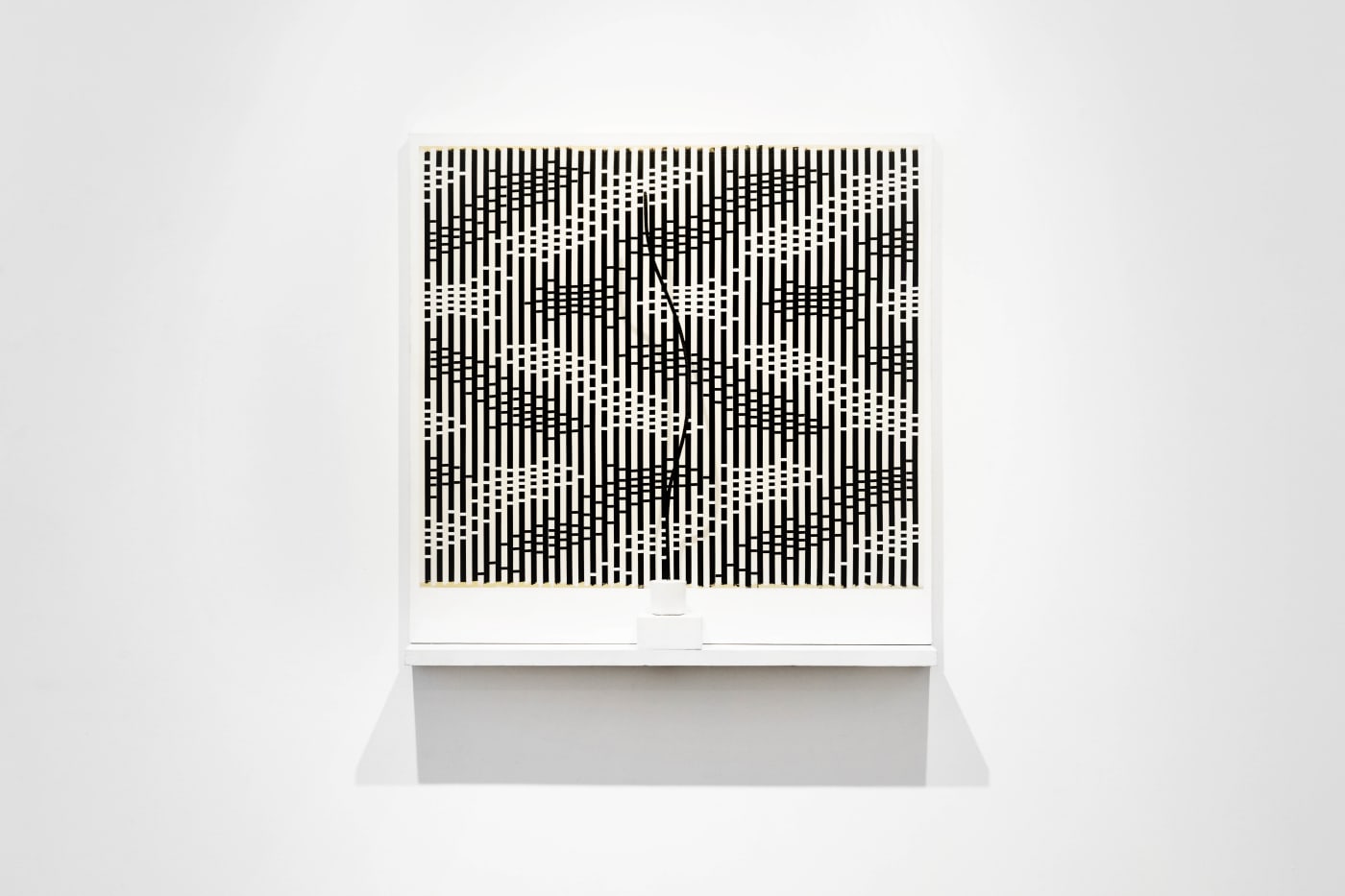

In a 1996 interview, Kidner indicated that 1970 was the year he deserted colour, coinciding with the development of dimensionality in his work. Kidner made a column form in 1969 manufactured from a sculpture of a wave, visualised in Column in front of its own image (1970). The imagery manifested through Kidner’s interest in number theory as the solution to the characteristic of order and the formation of reality. He translated the column into a two-dimensional form to a painting by employing a structured technique of measurement and colour coding. Since Kidner did not have a reference for the point of contact between two wavy surfaces conjoining at right angles, he bent a piece of wire to replicate a wave, and then rotated it at right angles, bending it to mimic the other side. To create a painting of a three-dimensional object, he had to view the object from all angles and document its silhouette as it revolved. The complexity of the column’s structure is further emphasised through the flickering monochrome contrast between black and white.

Enquire

Highlights from Maggie's Centre

. (This link opens in a new tab).chcjdgckAn dslahf;lshAn independent charity supporting those impacted by cancer diagnoses, Maggie's works with some of the most renowned architects in the world to design their centres with an awareness that light, colour and a connection to nature can help people to feel better. Later works by Michael Kidner were selected for Daniel Libeskind's design for the recently-opened Maggie's Centre at the Royal Free Hospital, London. (This link opens in a new tab)..

By the beginning of the 21st century, Kidner had turned his direction towards investigating the pentagon, galvanized by literary material including the 1989 book The Emperor’s New Mind by Roger Penrose, who explores the repetitive pattern found in Islamic temples as an allegory for order. The foundation of these later works is a web of connected pentagons constructed from outlines and networks, indicative of disorganized and tumultuous whirlpools that appear and recede as they are viewed. Kidner saw the pentagons as correlating with his uneasiness with the validity of religion as compared to the unpredictability of science. Born into a culture that relied upon the certainty of religion, the evidence of science undermined this comfort, forcing Kidner to confront a dynamic world filled with unpredictability.

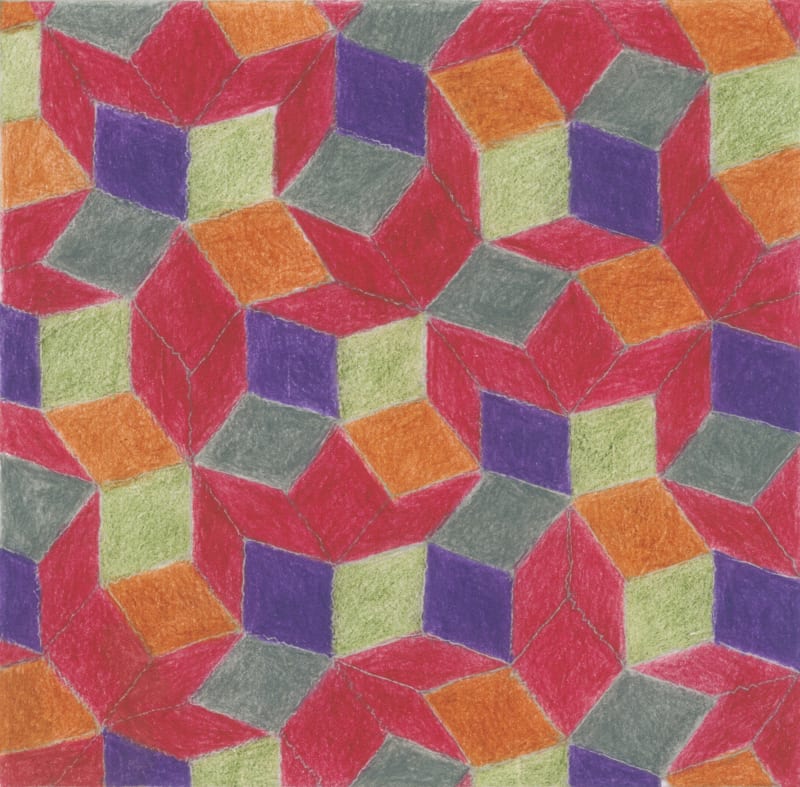

Prints from 2011 further demonstrate Kidner's preoccupation with pattern and mathematics towards the end of his life. Bursting with colour, the works are constructed from diamond shapes, employing deep and bright tones and shadows to make the shapes appear three-dimensional. The repetitive colours allow the characteristics of the form to be reinforced, imagined into an ordered organic structure of its own.

About Michael Kidner

Michael Kidner, RA (1917- 2009) was born in Northamptonshire, UK. He studied History and Anthropology at Cambridge University, UK, and Landscape Architecture in Ohio, USA, before joining the Canadian Army during WWII. After the war, Kidner returned to the United Kingdom, and embarked on a career as an artist. His work was first displayed in New York in 1965 in The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art, a group exhibition that subsequently toured the United States; and then in a solo show at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, in 1967. During the 1960s Kidner was associated with the Systems group of artists and was included in an Arts Council touring exhibition of Systems art in 1972–73 that originated at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London, some of which was displayed at Tate Britain in 2016. A retrospective at the Serpentine Gallery, London, in 1984 introduced a new generation of British artists to his work, and he was elected as a Royal Academician in 2004. A retrospective Love is a Virus from Outer Space took place at Daugavpils Mark Rothko Art Centre, Latvia in 2021-2022. Kidner's work is represented in public collections including Arts Council England, British Council, Government Art Collection, and Tate, UK; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon; and Muzeum Sztuki, Lódz, Poland.

For further information or to arrange a viewing please enquire below

Enquire